Local users and global resources

Digital technologies have changed libraries, access to information, and indeed the world. The information landscape has been revolutionized, especially for academic and scholarly resources in university libraries.

The library is no longer confined to a physical space. Access to library resources is often available throughout the university campus, or on the mobile device of the student or researcher. The transformation is now affecting daily lives with digital access to mainstream materials in public libraries, including online newspapers and popular e-book titles.

New ways to communicate and learn have enhanced education and classroom teaching, such as the creation of secure virtual learning environments.

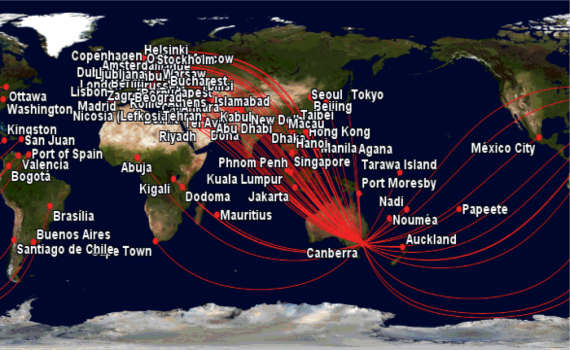

Libraries support the work of scientists and scholars that is increasingly collaborative, inter-disciplinary and global. As new opportunities for search and resource discovery are enabled by the internet, there is a growing demand for access to materials held in libraries in other countries.

WorldCat, an online union catalogue searches the collections of 72,000 libraries in 170 countries in multiple languages for all kinds of physical items, and new kinds of digital content [1]. There are article citations, authoritative research materials, such as documents and photos of local or historic significance, and digital versions of rare items that aren't available to the public [2].

Librarians are also collaborating with each other. Preservation and digitization - a core function of libraries – is an expensive operation. Therefore to lower the costs, most of which are funded from the public purse, and to reduce duplication of efforts, libraries are exploring opportunities for shared preservation infrastructures both within a country and with neighbouring countries, using new technological opportunities.

New technologies are also enabling libraries and archives to give access to material of social and cultural value to people in countries with shared histories. For example 'E-archive' is a joint project in Estonia, Latvia and Russia that brings together digitized collections of important material, such as the printed heritage of Latvia, that is scattered across institutions in Estonia and Russia. However due to copyright restrictions, such projects often have to limit themselves to older last century materials that are in the public domain [3].

"The borderless nature of digital technologies means it no longer makes sense for each EU country to have its own rules for telecommunications services, copyright, data protection, or the management of radio spectrum." European Commission priority Digital Single Market

Global resources and national laws

So how do national copyright laws that govern many of these activities look from the point of view of libraries today? Here are some of the facts.

The majority of member states of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) have one or more statutes that constitute a “library exception” i.e. 82% or 153 countries of the 186 countries surveyed [4]. This is good news. However, less good is the fact that 17% (33 countries) still have no provision at all for libraries in their copyright law, including six EIFL partner countries.

Look a little deeper, and the picture becomes somewhat more complex. In 18% of countries (34) the exception is in the form of a general provision only. Without specifics about scope and application, this can mean that libraries are left uncertain about their ability to digitize and preserve collections and to make them available for education and scholarship. With the result that the material tends to remain locked away or is available only to those who can physically visit the library (that is hard for many people nowadays to understand).

Exactly half (93 countries) permit libraries to make copies for research or study, and 53% (100 countries) permit copies for preservation. Or viewed the other way around, half do not explicitly allow copies for research or study, and 47% do not permit copies even for preservation purposes.

The figures for inter-library document supply – where a library provides a copy of a document to another library in response to a request from an end user – are even worse. According to the study, only 10% (19 countries) permit document supply, and 5% (9 countries) permit inter-library lending. Yet as noted above the demand for access to materials held in other libraries, including in other countries is growing.

“Not licensed to fill”

“Not licensed to fill” is a phrase encountered every day by librarians around the world. It means that a request for a document that is not available in the user’s home library is denied by the supply library due to licence restrictions.

In one example, a medical student requested an article published in a specialist medical journal that reviewed the literature of surgical techniques and outcomes for certain preoperative procedures. While the library subscribes to many databases, they do not have access to this particular journal. Although the supply library, that is located in another country, has the article, the licence does not permit it to be shared even with a sister institution that is part of the same network. This is why the law needs to step in.

For those with credit cards, the article can be purchased online for $35.95 or to put it in context, the equivalent of the cost of a local public transport ticket for three months.

As national laws are being updated, maybe the situation will improve? Unfortunately the trend regarding digital services suggests otherwise. For those countries that have introduced amendments since 2008, digital copying is expressly barred in more than 50% even, in some cases, for preservation.

And in countries with new anti-circumvention protections, while some 40 countries have thankfully exempted libraries, half have provided no library exception. The effect is that where a technological protection measure is applied to digital content, the library simply cannot avail of its exception. This means that in practice, the law is giving with one hand, and taking away with the other.

National laws and 186 varieties

The WIPO study throws up a further layer of complexity that permeates all the statutes, as the conditions for who may copy, what may be copied, the purpose and the format of the copies varies significantly. Here are some of the variations:

| Who may copy? | What may be copied? | Under what conditions? | How? |

| Libraries that receive public funding Publicly accessible libraries Public libraries All libraries |

Published or unpublished |

Library needs Research or study only Proof of user’s purpose Commercial availability Making available on the premises |

Electronic copies On any media Reprographic reproduction Reproduction by photographic or analogous processes Photocopying or with the aid of other technical means other than publishing |

186 varieties – time for one global framework

As libraries strive to provide effective information services to their local communities in a global information place, the laws that govern access to copyright protected content look increasingly unmanageable.

How might the law become more workable for librarians, archivists and other information professionals today?

In his presentation at WIPO's Standing Committee on Copyright and Related Rights (SCCR/29) Prof. Crews noted the influence of models in national law-making, such as UNESCO’s Tunis model law (1976), the Bangui Agreement, the so-called British model and the influence of European Union laws.

However, as each model is different, and as each country chooses its own elements to apply, at best a degree of partial or regional harmonization can be expected to be achieved. And the Internet is not regional.

“WIPO is in a position to shape the next model”, said Prof Crews. "To provide guidance to help countries develop statutes that are cognizant of the technology, and the growing range of library issues and activities. And that are cognizant of the fact that information exchange is crossing borders".

Libraries believe that WIPO, as a multilateral organization that sets international copyright rules, has a responsibility and a mandate. This is why libraries and archives are asking WIPO member states for an international treaty to establish basic global standards to ensure equal treatment of digital resources, to protect the ability to acquire and lend digital collections, and to safeguard our cultural and scientific heritage in the digital environment.

Countries will still have the ability to craft provisions that exceed the basic standards. Licences will still have an important role to enable activities that go beyond what is permitted in the law. But there will be a common global understanding that protects core library activities in the digital environment. That recognizes how technology is changing the way that people seek information, and the way that libraries respond to people's needs.

"Very few countries have a provision on inter-library loan. Very few countries have protection in the remedies for liability that librarians may face. Virtually no countries have addressed the issue of cross-border transfer of content. There is also an uneven application of digital technologies. And digital technologies, if they are not inevitable today will be inevitable in every country in the near term. So it's something that we simply need to face up to", added Prof. Crews.

Limitation on liability

Librarians need to understand and apply the law. Few librarians have had formal legal training, and most libraries do not have the financial resources to pay for specialist legal advice. So they often find the copyright rules confusing and intimidating, especially within an international context. From the evidence, it’s easy to understand why.

In a recent survey of 35 academic and public libraries by the EIFL Copyright Librarian in Serbia, not a single institution had access to professional legal advice. Therefore arguably one of the most important provisions needed by libraries is a limitation on liability that empowers librarians to take full advantage of the exceptions in national copyright law.

World Intellectual Property Day – the day on which the WIPO Convention came into force in 1970 – was designated with the aim of increasing general understanding of IP. What better way to celebrate than to give librarians, who in turn help others, the tools to understand and apply copyright law for the benefit of education, creativity and innovation.

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/WorldCat

[2] https://www.worldcat.org/whatis/

[3] Barbara Szczepanska EIFL Digital preservation and shared infrastructures: http://blogs.ifla.org/sccr/files/2014/05/side-event_FINAL-Barbara.pdf

[4] WIPO Study on Copyright Limitations and Exceptions for Libraries and Archives prepared by Kenneth Crews, J.D, Ph.D, Attorney at Law: www.wipo.int/meetings/en/doc_details.jsp?doc_id=290457

SHARE / PRINT